War Film Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/World_war_ll_the_movie_03012012_1_FLASH.jpg)

On a Sunday morn in march 1942, the commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces was sitting in his Washington, D.C. office with Jack Warner, vice president of Warner Bros. Studios. The U.s.a. had entered World State of war Two the previous December, and Lieutenant General Henry "Hap" Arnold had spent the past four months shaping his air force into ane of the most formidable in the world. Anticipating an air war on 2 fronts on opposite sides of the globe, the service was rolling out tens of thousands of new airplanes. Arnold needed men to fly them.

Arnold wanted 100,000 pilots, and he told Warner he needed a powerful recruitment picture show. Afterward that, he'd need constructive training films to get all those recruits flying and fighting as soon equally possible. To make all these movies, he proposed building a USAAF picture unit, staffed entirely with recruits from Hollywood.

Also in the room during that meeting was Owen Crump, a scriptwriter with a reputation, adult during a career in radio, for speed and accuracy. Since before Pearl Harbor, he and Warner had been making propaganda films for the military, intended to promote the military to an American public reluctant to enter the war in Europe. Crump, who died in 1998, recalled the meeting in an interview recorded during 1991 and 1992 by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. He remembered that after Warner agreed to throw his studio's weight behind the thought, Arnold turned to Crump and said, "You're in this too"; he promised both men officers' commissions on the spot.

On the plane back to Hollywood, Crump wrote the script for Winning Your Wings, the recruitment film Arnold had commissioned; inside days, information technology was in product. John Huston, who had recently fabricated The Maltese Falcon, was brought on to direct it. Actor Jimmy Stewart, an accomplished pilot who had enlisted the previous year, was given orders to star as the film's on-photographic camera narrator. Stewart took his service in the Air Forces seriously, and thinking the studio had pulled him away for a publicity stunt, he arrived on set irate. Crump took Stewart across the street to a café and explained what he and Warner were upwardly to. Stewart apologized for the accident-up, knocked out his scenes in a few days, and flew dorsum to his post.

Winning Your Wings opens with Stewart flight aerobatics in a BT-13 Valiant trainer, which he then lands and taxis upwards to the camera. He radiates cool in his leather jacket and aviator sunglasses, and he waxes poetic about the importance of winning the war. The scene cuts to a young actress ditching her ground-spring Regular army date for a boy with wings on his jacket, as Stewart's vocalism-over claims that flyboys ever get the daughter.

The film played in theaters all over the country—and more than 150,000 men signed upward to bring together the Air Forces.

Requests from Washington for more than recruitment movies started to pile upwards, and Warner and Crump realized the studio wouldn't be able to satisfy its military obligations on top of its normal production schedule. They decided Crump would put together a separate studio devoted to serving the Air Forces. Warner gave Crump the idle Vitagraph Studios lot, where silent films had been fabricated in the 1910s, and Crump set out to plough information technology into a military postal service.

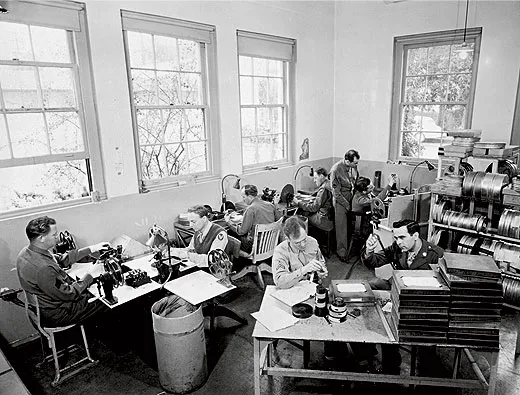

Crump began recruiting from the Hollywood studios. A few other notable filmmakers, like managing director Frank Capra, had already joined the service (Capra was in the Army Signal Corps, which also made training and propaganda films), and Crump didn't want all the good talent to enlist before he got his unit off the basis. He put an advertizing in the trade papers, and by the next 24-hour interval his role was flooded with applications from writers, directors, editors, animators, and composers, many of whom were established professionals willing to accept a sizable pay cutting to join the war effort. Future best-selling novelist Irving Wallace wrote scripts. Artist Wayne Thiebaud painted sets. Larry Ornstein, a trumpet player for the big bands, recorded the reveille that played each forenoon on the mail service public accost arrangement.

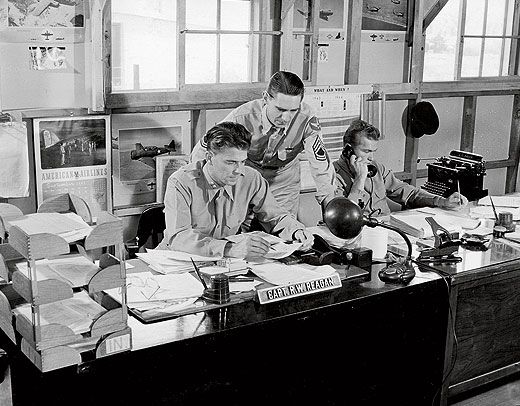

Several motion-picture show stars joined the unit as well: Clark Gable, Lee J. Cobb, William Holden, Arthur Kennedy, Van Heflin, Joseph Cotten, DeForest Kelley, Alan Ladd, and others. Westerns star George Montgomery drove the bus from the billet to the post. Actor and future president Ronald Reagan, who was already a second lieutenant in the Cavalry Reserve, transferred to the Air Forces to join Crump's outfit. He was well liked in the movie industry, and so Crump made him the unit's personnel officer and put him in charge of processing incoming recruits.

On July 1, 1942, the outfit was officially named the Army Air Forces Outset Movement Picture Unit. But Vitagraph was underequipped for total production, and Crump struggled at first just to supply the post with the basics. Luckily, his men were used to improvising. "Motility picture fellows, a lot of them, are very, very skillful at that," said Crump, remembering how the men brought whatsoever was needed from their own homes. "These are the things I'm so proud of, the mode the thing got started."

But the unit still needed a proper studio. As Crump drove past Hal Roach Studios in Culver City, where the Laurel and Hardy and Our Gang films were fabricated, he noticed the lot was out of employ (Roach had been conscripted into the Signal Corps in Astoria, New York, forcing him to put his studio's lineup on hold). The studio had everything the movement picture unit needed: six warehouse-size sound stages, prop rooms, editing trophy, costume and makeup departments, fifty-fifty an outdoor gear up made to look like a city street. Crump called Arnold, and inside eleven days the Air Forces had leased the studio and made production manager Sidney Van Keuren a major. Jack Warner, feeling he'd done his part getting the outfit off the ground, went back to running Warner Brothers.

Crump moved his unit from Vitagraph to Hal Roach Studios, which they dubbed Fort Roach. The lot comprised 14 acres and dozens of buildings, virtually of them windowless to provide the controlled-lighting environments necessary for filming. The exception was a long, narrow two-story building in the front end of the lot that contained the post's production department. Crump moved into Hal Roach's one-time office, which was decorated with chandeliers, dark wood paneling, and ornate molding and which, in the studio's early days, had contained a polar bear pelt.

Bated from the military motor pool in the back of the lot and the fact that anybody was in uniform, Fort Roach looked and functioned similar a conventional movie studio. The only thing it didn't have was a mess hall, so the Regular army built 1. The barracks, which housed the men who didn't have homes in Los Angeles, were located two miles abroad, at Page Military University.

In addition to their filmmaking work, the men shared KP duty in the mess hall and took turns guarding the studio'south front gate. Each forenoon they would march in groups downwards Washington Boulevard to perform calisthenics in the parking lot of the Casa Mañana nightclub. People began to call them the Hollywood Commandos, and the men adopted the motto "We kill 'em with fil'm."

The unit's beginning official project was a training film called Learn and Live. Information technology is fix in "Pilot's Heaven," where uniformed fliers wearing white angel wings mill around in the afterlife while their instructor tells St. Peter what flying errors they made to end up there.

Not all of the unit'southward piece of work was and so fanciful. Many of its projects demanded the distillation of complicated details so they could be learned quickly, like the movies the unit of measurement made on how to identify enemy aircraft. This grooming was amid the most vital that American airmen received.

In the Pacific, American pilots couldn't tell the difference between a Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero and a U.Due south. Curtiss P-forty Warhawk, and were shooting down their wingmen. An intact Zero was finally captured in Alaska, and was immediately loaded into a cargo plane and flown to Los Angeles, where unit cameramen were waiting. Within hours the Nothing was doing maneuvers over the Californian desert every bit camera planes filmed information technology from every bending. The blitheness department worked through the night to develop a unproblematic style of illustrating the Zero's distinguishing characteristics. A finished film on how to identify the enemy airplane—consummate with a cartoon comparison the fuselage to a cigar—was shipped out to air bases all over the Pacific theater the next twenty-four hours.

Howard Landres and Eugene Marks, now in their late 80s, are among the few alumni of the unit of measurement nonetheless living. They were babyhood friends in Los Angeles, and they were only 19 when they joined the Air Forces equally filmmakers. Both were going to higher and working part time, Marks as an engineer at a recording studio and Landres in the reading room at MGM. Having heard that the Air Forces had formed a film unit of measurement close to abode, they jumped at the hazard to join. Landres showed up to interview with Lieutenant Reagan on a Thursday (his day off at MGM), and Reagan asked if he would be set up to join the Air Forces the next mean solar day.

"I said, 'Tomorrow's Fri! I have a appointment,' " Landres remembers. Reagan suggested the following Tuesday, and they had a deal. Marks as well asked that his induction be postponed a few days, every bit he had tickets to a football game.

"You got to remember, this was a Hollywood unit," says Landres. "Nobody really saluted as an officer passed. I mean, information technology was so non the military." Many members of the unit of measurement lived at abode and commuted to Fort Roach. The men addressed one some other by outset names, and in their gratis time they played badminton or volleyball on empty sound stages. All unit recruits were required to get through basic preparation earlier reporting to the postal service, says Landres, "but it wasn't the basic-basic."

"It was like, marching upward and downwardly the street for 20 minutes," says Marks.

"How we won the war was non through this unit," jokes producer Arthur Gardner. "If whatsoever real Regular army officer had come and spent a week there, he'd have been out of his mind." Gardner, now 101 years old, had been an role player in the 1930 pic All Quiet on the Western Forepart, and already had an established producing career when he joined.

But there was serious business organisation going on at Fort Roach. Several of the unit'south films were top secret, and during filming and editing, parts of the mail were restricted. Marks remembers being issued a sidearm and ordered to accompany a batch of celluloid from the lot to a nearby processing facility. Afterward he learned the film was function of a briefing on the atomic bomb missions to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

"We were pretty serious there," says Landres. "I mean…nosotros were still kids, only it was nonetheless a big war. The training films actually were important, and they're pretty well done. Because before that, there was really zip stimulating when y'all saw an Regular army movie for training."

An example of Fort Roach'south improvement to the military machine training experience was Resisting Enemy Interrogation, a feature-length thriller about a downed aircrew captured by the Nazis. The script is based on the experiences of 2 American airmen who had been held and interrogated at a chateau in southern Germany; ready designers modeled the interiors of the chateau later the airmen'due south memories of the existent thing, and took detailed notes on the Germans' tactics. The ready builders even enlarged a postcard of the chateau to employ equally a backdrop for the opening scene.

Owen Crump remembered that when the picture show was kickoff assigned, it had a palpable buzz. "Kind of similar in a regular motion picture show studio," he said, "sometimes you get involved with a picture show that everybody, the cameramen, electricians and the gaffers, the cutters, everybody, and the actors, know they got one. Everybody feels information technology and gets excited."

The film'southward purpose is to show airmen-in-training how wily interrogators can exist, and how catastrophic the consequences of talking. Information technology's riveting to watch. The dialogue, acting, cinematography, and music are all cranked up to Hollywood blockbuster-levels, a quality reflected past the film'southward nomination for an Academy Accolade in 1945 in the category of Best Documentary Feature.

While many of the unit of measurement's early films featured its famous actors onscreen, celebrities similar Reagan were eventually used only for voice-over, then as not to distract trainees. Instead, nigh members of the unit of measurement served as actors at one time or another. Crump remembers when a visiting colonel unwittingly saluted an electrician dressed as a one-star general for a scene being shot nearby.

To train bomber crews going to Japan, the fine art department built a ninety- by sixty-pes scale model of Japan's coast. The model was made out of paperboard, pigment, plaster, clay, and textile; forests were made out of foam that had been put through a grinder. During filming, the photographic camera would "wing" over the model to simulate the exact road of the flop runs. Pilots returning from Japan said the model was incredibly accurate, fifty-fifty downward to the varying colors of the seawater along the shore.

1 of the crucial functions of the unit of measurement was to railroad train gainsay cameramen in the use of motion film cameras on the battlefield. Some of the trainees were Hollywood cinematographers; some were high school kids who had taken photography classes. All had to be taught how to load their own film and, if the demand arose, how to develop information technology in the field. From Culver City, the cameramen would ship out all over the earth to record the war. In some cases, footage from the front was sent to Fort Roach for apply in its films. The men of the Combat Camera Units saw every type of action—they even trained to use machine guns in example a gunner was hit on a bombing run—and they were just as probable to be killed or wounded equally their fighting comrades. Much of the aerial footage of World War 2 was shot by crews trained at Fort Roach.

While filming the documentary Memphis Belle, Oscar-winning manager William Wyler and his photographic camera crew flew in bombers over Europe and saw flak and motorcar-gun burn down up shut. Wyler wrote home about the challenges of shooting film at 29,000 feet in an unpressurized, unheated cabin. They had to hug their cameras to keep them from freezing up, and getting a good shot was hard with the oxygen tanks they had to elevate from window to window—while under enemy fire.

Most of the picture show professionals at Fort Roach never saw that side of the war, though occasionally they came close. Writer/manager Stan Rubin, now 94, was sent to the Pacific island of Saipan to document the outset B-29 mission to flop Tokyo. While Rubin waited for the Superfortresses to leave, the Japanese bombed Saipan night later on night. No bombs directly threatened the foxhole where he took shelter, but it was the closest he ever came to combat. He remembered his relative rubber when interacting with regular servicemen who had seen the fighting first hand. "They were appreciative to a certain extent of what we were doing," he says. "Merely it would never live up to those who had been in combat or were about to go into combat."

According to Crump, the Surgeon General of the Air Forces claimed that a ten-infinitesimal picture fabricated past the unit could teach his men more about caring for the wounded than he could teach them in a month. In his memoirs, German Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel wrote of the American armed services, "Our major miscalculation was in underestimating their quick and complete mastery of film education." Partly equally a result of the training in which the Start Motion Motion picture Unit played such an essential role, more bombers and fighters were in the air over Europe faster than the Germans could organize to repel them.

When the state of war ended, the unit of measurement was disbanded, and Hal Roach Studios was returned to its possessor with several million dollars' worth of improvements, courtesy of the Army Air Forces. The studio went dorsum to making commercial films, merely eventually airtight. In 1963, it was demolished. Cistron Marks became a music editor, and worked on such varied films every bit The Exorcist and Spaceballs. Donald Meyer, a writer for the unit, went on to pen hundreds of songs, including the Billie Holiday hit "For Heaven'due south Sake." A few of Fort Roach's filmmakers stayed in the war machine, and some went on to pic the many nuclear bomb tests conducted past the United States throughout the common cold war.

When the Germans surrendered in May 1945, Full general Arnold gave Crump one terminal task: to travel throughout Europe shooting colour film of the impact Arnold'due south air force had had. Crump and his crew traveled from city to urban center, including Berlin, filming the harm washed by years of bombing. They recorded the interrogations of top Nazi officials captured subsequently V-Due east Twenty-four hour period. They shot footage of the Nazi concentration camps Ohrdruf and Buchenwald as Allied forces liberated the camps.

Back in California, Ronald Reagan and Technical Sergeant Malvin Wald, a scriptwriter, were among the few people to run into the developed picture show of the camps. "Fifty-fifty though it was a summertime day, Reagan came out shivering—we all did," Wald recalled in a 2002 interview. "Nosotros'd never seen annihilation similar that." Arnold was ultimately unable to procure enough funding from Congress to create a documentary using Crump's footage, and the unused raw picture was interred in archives.

After the war, Crump was asked to stay on to command a new pic facility existence set up in Florida. The Air Forces brass had been so impressed with the task he'd done at Fort Roach that they offered him the rank of general. Only Crump retired his commission and went dorsum to work for Jack Warner.

Crump remembered being on the Warner Brothers lot shooting a civilian moving-picture show when two Air Forces officers showed up. They had seen Resisting Enemy Interrogation in preparation. Overseas, they were shot down and captured in Germany. Afterward the downed airmen had been taken in a very familiar truck, through a very familiar gate, they looked at each other in disbelief. There was the verbal aforementioned chateau from the movie. "We'd die laughing," Crump recalled them proverb, "because it was but like the movies. We all felt similar we were in the movies."

Crump told them how the film was made, the tricks they'd used, and all the expertise and talent that had gone into it.

When they asked him how he knew so much virtually information technology, he didn't tell them that he'd congenital the First Motion Motion picture Unit from scratch, or that he had produced the film that helped them through their captivity. Crump replied only, "Oh, I was in the Air Force too."

Mark Betancourt is a author and filmmaker living in Washington, D.C. Owen Crump was interviewed by Douglas Bell, Academy of Moving-picture show Arts and Sciences Oral History Programme, 1994.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/world-war-ii-the-movie-21103597/

Post a Comment for "War Film Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences"